Managing a Product Roadmap

December 16, 2016

There are two important insights I want to share with fellow product managers:

- Understand the split between reactive development and feature development.

- Understand the split between a feature wishlist and a roadmap, and manage both proactively.

(I’m assuming software development with small release cycles, i.e. 90% of startups).

Reactive vs. Feature

Before you launch a product the development effort is feature driven. The vision gets turned into a design which defines the surface area of the user experience. Then the design gets turned into a functioning product; a sort of mold for experiences to flow through. Now starts the feedback process. Adjust design based on feedback. Rinse, repeat.

At the first feedback cycle you experience the draining feeling of lowered expectation. You’ll have to delay the features you hoped to start working on post-launch. This always happens.

Importantly, this will keep happening again and again until you acknowledge and proactively manage the split between Reactive and Feature driven development.

Reactive development is the effort spent fixing and adjusting the user experience. Bugs surface, unforeseen consequences eat into your development hours. And none of this work is as satisfying as Feature development. It has been my experience that more than a month spent in Reactive development can emotionally drain the team and contribute to unhappiness. None of it was “supposed to happen”. It wasn’t on the Roadmap, and it requires emotional toughness to plow through. But there are moments of pleasure, but more in the form of relief when glaring omissions are addressed and bugs are squashed.

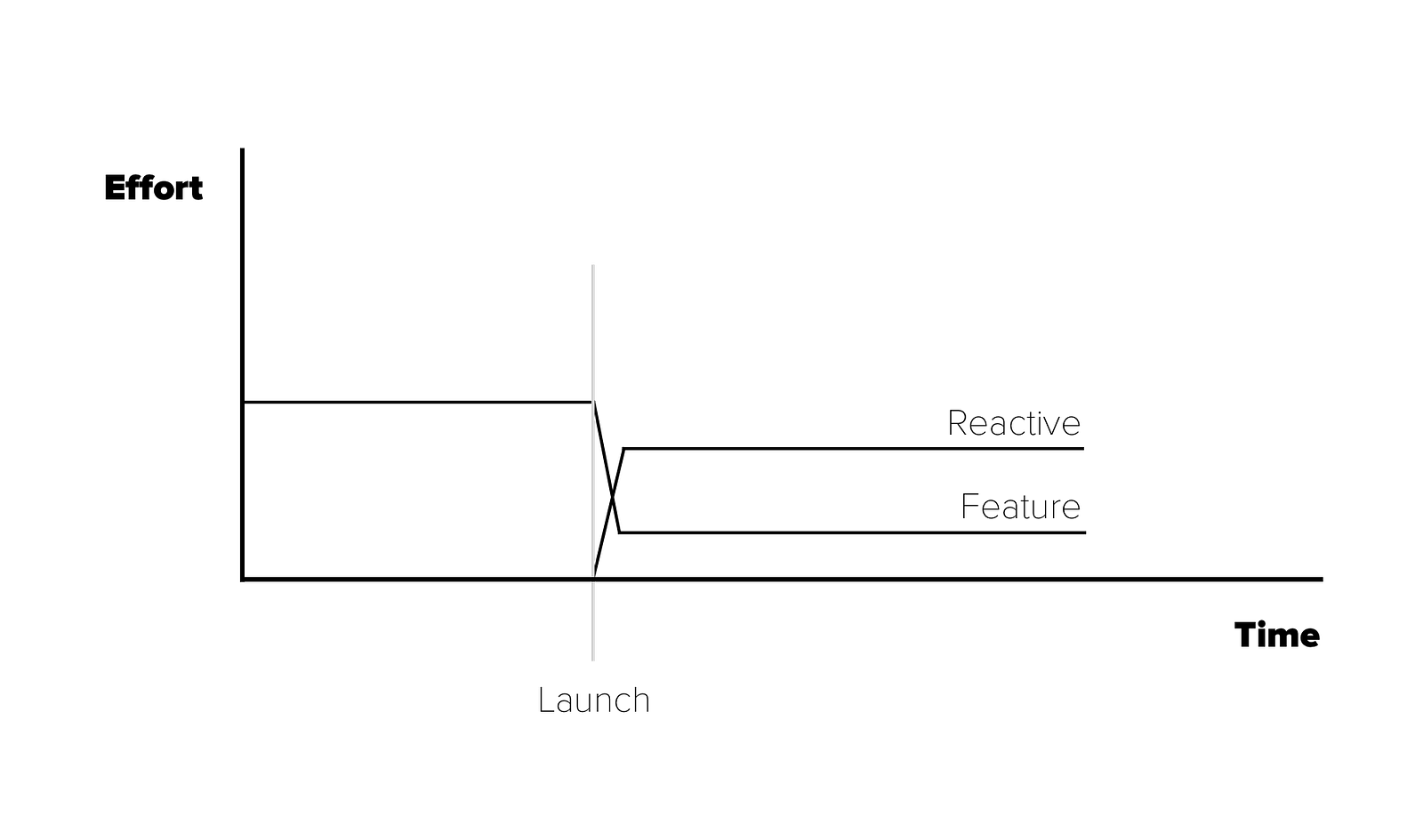

My advice is not to avoid Reactive work, but to account for it, time-wise and emotionally. The effort split is going to look like this, assuming constant workforce availability:

Approximate split between reactive and feature development over time and through product launch

Wishlist vs. Roadmap

A big part of product management is managing expectations. The entities you need to communicate with are:

- Users

- Internal Stakeholders

- Developers

The product vision will evolve through:

- Feature requests from users

- The business plan & strategic product iterations

- Developer and designer discussions

I recommend doing a “hard split” between your ideas and things you irreversibly commit to shipping, no matter where they come from. Formalise the ideas however you want (words, pictures) and put them on a Wishlist (we use Notion.so). Do this ad-hoc (as ideas surface), and make this part of your responsibility. Everyone should know you are the person to come to with product ideas and issues. Do monthly product planning sessions with your development team where you move things from the Wishlist to the Roadmap only when you and your team is confident about shipping said ideas in the coming future (say 2–3 months). Keep the Roadmap down to 5 items. This seems low. But it’s simply unfair to hold your development team accountable to that sixth item. There’s too much uncertainty to promise it. Your mind assumes 100% of development effort is spent on these things, but as you saw above only about 1/3 of it can to contributed to features.

The Roadmap is where you irrevocably hold yourself and your team accountable to developing and shipping a feature or product improvement. And it doubles as a tool to exchange information about what is actually being worked on and what is actually getting shipped. This is also where you prioritise and ask your developers to become accountable for dates (without being a jackass, engineering uncertainty is what it is, meet somewhere in the middle).

Make sure internal stakeholders and developers understand the difference between a wishlist and a roadmap

Armed with these two insights you will be able to make increasingly accurate predictions, and more importantly manage expectations of your product stakeholders.

I am the co-founder and product manager of Takumi. We make the influencer-first marketing platform. We run our product development in Reykjavík, Iceland.